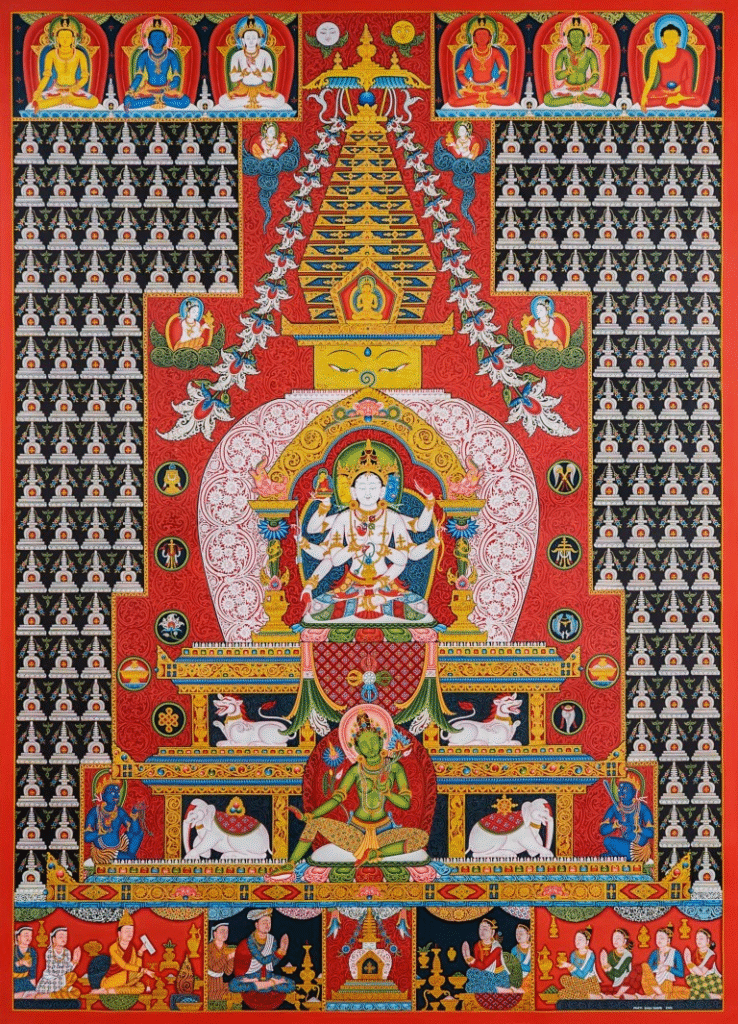

Thangka is a sacred traditional art form in Buddhism, primarily practiced in the Himalayan region. This artistic tradition thrives in Nepal, Tibet, Mongolia, Northern India, and Bhutan. In Nepal, it is known as Paubha, a term derived from “Patra Bhattaraka,” which means “painting on cloth.” These scroll paintings serve as visual representations of fully awakened beings and embody Buddhist teachings, making them more than mere artistic expressions.

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to Nepali Thangka art. It covers spiritual and cultural significance, artistic history, and the process involved in its creation. The article also discusses the care, preservation, and challenges faced by this practice across the Himalayan region, emphasizing the role of artists, cultural institutions, and community efforts in safeguarding Thangka as a living spiritual heritage.

Why are Thangkas painted?

People often commission or paint Thangka to gain spiritual merit. They believe that creating a Thangka helps:

- Remove physical or mental obstacles.

- Promote health, longevity, and recovery from illness.

- Practitioners use Thangka to guide the deceased towards a favourable rebirth.

- Accumulate merit for spiritual advancement.

Significance of Thangka Art

For centuries, practitioners have used Thangka to visualize deities during meditation, internalize their qualities, and deepen their understanding. Thangka also holds prominent positions during philosophical discourses, teachings, and tantric practices. Additionally, they commission Thangka to mark significant events such as festivals or celebrations. People also use them during ceremonies, empowering rituals, and processions to invoke specific blessings.

Practitioners often refer to Thangka as a “roadmap to enlightenment” and a “recorded message.”

They consider Thangka to be:

- A visual guide to spiritual liberation.

- Visual books that communicate complex religious, and philosophical doctrines and cosmologies through symbolic imageries.

- Record of Himalayan cultural heritage, embodying historical narratives, artistic lineages and legacy.

- Devotional objects created for veneration, placed within altars and ritual spaces to enhance spiritual practice.

- Decorative elements within temples, monasteries and residences serving both aesthetic and sacred functions.

Development of Thangka Art in Nepal

Nepal historically served as a crucial cultural and trade bridge in South Asia. It fostered strong political, religious, and economic ties with neighbours in the Gangetic plains to the south and the Tibetan regions to the north. This strategic position connected major trade networks like the Uttarapatha, Dakshinapatha, and the Silk Road, enabling Nepal to prosper economically and culturally from early times. This connectivity enabled Nepal to play a key role in spreading Buddhism and to serve as a gateway for merchants, pilgrims, and scholars traveling between India, Tibet, and China. This vibrant exchange of ideas, artistic traditions, and trade strengthened Nepal’s unique identity, making it a vital crossroads for Himalayan Art.

Tradition of Paubha and Thangka Painting

Thangka and Paubha paintings are among the various artistic practices that have a rich tradition in Nepal. However, the early history of this art form remains largely unclear. The medium’s (cotton canvas) delicate nature makes the artwork fragile and difficult to preserve over time. Artists rarely signed or dated their works, as they followed strict spiritual and artistic guidelines that prioritized devotion over personal recognition. People also often replaced both the paintings and their mountings when damaged, further complicating efforts to establish a precise historical context or chronology.

Nepali painting of Ratnasambhava from the 12th century at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.Scientific Dating and Early Nepali Paintings

Carbon dating has shed some light on the antiquity of Nepali artworks. The earliest carbon-dated paintings of Nepal include those of Ratnasambhava (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), Vairochana, Amoghsiddhi, and Arya Tara (The Cleveland Museum of Art), all dating back to the 12th CE. Similarly, the earliest painting with an inscribed date is the Mandala of Vasudhara from 1365 CE (in a private collection).

Distinct Iconography and Artistic Evolution

Some scholars speculate that Paubha and Thangka art may have evolved from cave murals of Ajanta and Elora in India. However, scholars including John C. Huntington, Dina Bandgel and Pratapaditya Pal hold differing views. Bangdel and Pal argue that ancient Buddhism existed in Nepal and that artists borrowed only the basic concept from India. They emphasize that Nepali artists developed their own distinctive iconographic deities that were not familiar in Indian traditions. Furthermore, from the 7th to 13th CE, Nepal profoundly influenced Tibetan artistic traditions.

What makes Thangka a Sacred Art?

People regard Thangka painting as a source of merit that benefits both the patron and artist. By commissioning or creating a thangka, individuals seek to generate spiritual merit and receive blessings.

Many people believe that performing this noble deed leads to positive outcomes such as:

- Good health and prosperity

- Alleviate suffering

- Grant a noble rebirth with mastery over the senses

- Bestow radiance and an appealing presence

- Victory over adversaries

- Enlightenment

Fundamental Concepts of Thangka Paintings

Thangka painting is a highly specialized discipline that adheres to strict traditional guidelines concerning iconography (the interpretation of visual images and symbols) and iconometry (a system for measuring body proportions). Artists must maintain intense focus, pay close attention to detail, and possess a profound understanding of Buddhist, Hindu, and Bon philosophies.

Process of Creating Thangka Paintings: Materials and Techniques Used

The process of Thangka painting involves several steps. Artists begin by preparing the canvas, stretching and priming cotton or silk fabrics. They then trace or sketch, color, outline, apply gold and silver, and polish the painting. Finally, they complete the eye-opening and face painting. Once finished, they mount the painting on silk brocade or frame it.

Traditionally, artists paint Paubha and Thangka on handmade cotton or silk canvases using natural pigments derived from plants and minerals. While this practice still continues, modern artists have also started to incorporate specific regional styles with subtle shifts in the composition, medium, and color palettes.

Types of Thangka

Thangka paintings can be classified in several ways based on their background colors, materials, techniques, and regional traditions. These categories help identify the purpose, symbolism, and artistic lineage behind each work.

Based on Background Color

- Tson-thang (tson refers to color)

- Ser-thang (Yellow or gold background, also known as Serti, with details in color)

- Tsal-thang/ Mar-thang (Red background, also known as Marti, with details in color, gold, and silver)

- Nag-thang (Black background, also known as Nagti, with details in color, gold and silver)

Unique technique and materials

- Appliqué and embroidered

- Traditional methods

- Modern methods

Country Based

- Tibetan

- Nepali (Paubha)

- Mongolian

- Japanese

- Korean

- Chinese

- Bhutanese

Thangka styles based on Region and School

The Thangka painting tradition evolved through strong cross border interactions, local artistic practices, and direction of specific teachers or master artists. Regional access to particular pigments and materials, along with the preference of patrons also shaped how Thangka developed.

Early Thangka compositions drew heavily from Indo-Nepali style, which later merged with the Kashmiri Khanche style and incorporated Tibetan Beri (Bal-bris) and eastern Indian Pala aesthetics. By the 14th century, Chinese landscape tradition began to appear in Thangka landscape, adding vivid naturalistic depth. Between 17th and 18th CE, artists started depicting architectural subjects such as palaces, monasteries and hermitages.

Over time, artists developed distinct schools of Thangka art, including the Kadampa, Beri, Menri, Mensar (new Menri), Karmagadri, Repkong, Ngor, Chamdo and Chanti style. Each characterized by unique languages and regional interpretations of Buddhist philosophy and iconography.

Iconography in Thangka

Artists created Thangka paintings based on canonical texts (pecha) such as the Silpasastra and Pratimalakshan. These texts describe religious figures, including their proportions, colors, postures, and gestures. Important scriptures, such as the Manjusrimulakalpa Tantra (an 8th-century Vajrayana text that provides extensive descriptions of paintings, such as pata), along with Chitralakshan, Sadhanamala, Nispannayogavali, and Newari manuscripts like Thyasafu, elaborate on the iconographic principles of deities.

Generally, Thangkas are categorized as lineage paintings, astrological and cosmological charts, sacred geometry diagrams, narrative paintings, Buddha fields, traditional medicine, ritual paintings, and spiritual figures. They further classify figures as teachers, Arhants, Buddha, Bodhisattva, Tara, Yidams, Dakinis and Yoginis as well as protectors and guardians.

Who creates Thangka paintings?

People often assume that Thangka artists are exclusively monastic monks, but this isn’t entirely accurate. A layperson from any established artistic lineage, community, or family can also be a Thangka artist. These artists receive extensive training, either in monastic institutions or through the traditional Gurukul apprenticeship system, where masters pass their skills on to students.

Artists master various painting techniques, as well as the study of iconography and iconometry, alongside Buddhist philosophy. They learn to distinguish between higher and lower tantra subjects and accurately depict deities as described in canonical texts. In Nepal, Thangka paintings are created by artists from the Tamang, Hyolmo, and Sherpa communities, while the Newa community specializes in painting Paubha.

The Ritual

Thangka and Paubha artists view painting as a form of spiritual discipline. They perform specific ritual steps to preserve the sacred nature of their work. Master artists often undergo initiations and receive empowerments, which include the ritual of Hastapuja (hand worship), before starting their practice. According to Vajrayana Buddhism, artists who depict deities belong to one of the four classes of Tantras, and thus, they must be ritually initiated into each class. However, in everyday practice, very few artists adhere strictly to this routine.

Some of the integral practices followed during thangka painting are purification rituals, meditation practices, eye-opening ritual, and application of gold. They often inscribe the sacred syllables “OM AH HUM” on the back of the painting, symbolizing the deity’s enlightened body, speech, and mind.

Once completed, the thangka undergoes a consecration ritual led by Buddhist monks. This ceremony dedicates the painting’s merit to the patron, their family, and all sentient beings. Sometimes, revered teachers place their handprints on the back of the thangka as a final blessing.

Through these rituals, thangka paintings transcend mere artistic expression and become spiritual conduits, capable of inspiring devotion and facilitating deeper Buddhist practice.

Placement of Thangka

Traditionally, practitioners hang either framed or silk-brocaded Thangka against solid walls in a clean and well-lit area, avoiding windows or mirrors. Thangkas should always be placed at eye level or higher, but never below, as this is considered disrespectful. They usually face Thangka east, except for those with designated directions such as west for Amitabha Buddha, north for Amoghasiddhi Buddha, south for Ratnasambhava Buddha, and east for Akshobya Buddha. The same rule applies to the Four Guardian Kings, as well as the Eight Guardian Deities. However, when uncertain about direction, one can face the thangka towards the East direction.

For consecrated Thangkas, practitioners often create a small platform or altar beneath or in front of the painting to offer items such as Khada (ceremonial scarves), water, a butter lamp, and incense. More elaborate setups can also be arranged. However, if the Thangka is not consecrated, this step can be skipped. While Thangkas can be displayed in most rooms, it’s best to avoid placing them in bathrooms and kitchens to maintain purity and prevent exposure to moisture. Ideally, Thangkas should be kept in meditation rooms as well as living areas. In Nepal, practitioners typically keep Thangkas depicting personal tutelary and tantric deities private for their practice.

Care of Thangka

Thangka paintings are inherently delicate and fragile. To prepare a Thangka canvas, artists use refined white clay mixed with animal skin glue on cotton canvas. This composition causes the canvas to respond quickly to environmental conditions, such as temperature and humidity, and makes it susceptible to pests. The pigments used in these paintings are typically natural mineral and vegetable colors, and sometimes include chemical colors. Since there is no chemical treatment to enhance durability, the paintings are prone to fading or discoloration when exposed to direct sunlight or ultraviolet (UV) rays. They are also vulnerable to pests like moths and rats. Therefore, regular cleaning, careful handling, and maintenance are essential to ensure their longevity.

Environmental Risks

- High Temperatures: In hot conditions, like summer, the Thangka can dry out, causing cracks in the paint.

- Humidity and Moisture: During monsoon or humid weather, the canvas absorbs moisture, which may lead to distortion of canvas as well as mold growth.

- UV Rays: Pigments used in Thangka are sensitive to sunlight, which can cause fading of exposed areas gradually.

Protecting and Displaying

To minimize damage from environmental factors:

- Frame the Thangka with adequate space between the painting and the glass to reduce exposure.

- Avoid direct sunlight and harsh artificial lighting.

- Ensure proper ventilation around the artwork.

Cleaning Thangka Painting

- Framed Thangka: Routine cleaning of the frame and glass with regular de-framing and feather dusting of artwork helps to maintain the condition.

- Unframed or brocaded Thangkas: Use a feather duster to gently remove dust from the painting surface, while a soft brush and a low-level vacuum cleaner are suitable for cleaning silk or fabric brocade.

- Avoid Washing or Dry-Cleaning: Never wash or dry-clean a Thangka as this can cause irreparable damage.

Proper Storage Practices

- Maintain a clean, dry environment with stable humidity around 40-50% to prevent both dryness and excessive moisture. This practice also prevents fungal growth.

- Treat storage areas with smoke or chemical treatments as needed to prevent fungal growth and termite infestation,

- Smoking the painting can also prevent it from infestation and rodent attacks.

- Roll unframed Thangka loosely with protective layers of acid-free paper (such as Nepali paper) or cloth to avoid creases.

When to Consult Professionals

- Visible Damage: Noticeable cracks, tears, or flaking paint on the surface of the Thangka

- Severe Discoloration: Rapid color fading beyond normal light exposure.

- Structural Weakness: If the canvas becomes brittle or distorted.

- For Authentication and Documentation: When there is a need to confirm the artworks authenticity and provenance.

- For Long-term Preservation Plans: Especially for old, fragile Thangka and Paubha paintings.

Challenges faced by Thangka Paintings

Thangka and Paubha paintings represent some of Nepal’s richest cultural and spiritual traditions. Yet today, these art forms confront multiple challenges that threaten their survival and integrity. Understanding these issues helps us to address them.

Political and Economic Pressures

Political unrest, combined with ongoing global economic recession, and the lasting effects of the 2015 earthquake and COVID-19 pandemic, have severely disrupted Nepali art scene. These challenges have reduced the number of young artists entering this field. Many artists rely on tourism, exports, and private commissions, but unstable art markets and cheap mass produced works undermine the value of authentic artworks. Limited financial support and patronage further threaten the sustainability of this sacred art tradition.

Apprenticeship System and Youth Engagement

Thangka painting was traditionally passed down through long apprenticeships under master artists within monastic and family settings. However, many young artists today choose short-term training aimed at employment or commercial production rather than mastery. As fewer young artists are willing to master this art form, the transfer of traditional knowledge, discipline, ethics, and ritual practices that defined this art form is increasingly endangered.

Limited Public Recognition and International Representation

Popular galleries in Nepal rarely recognize or represent traditional artists. They also lack representation in the international art scene, which restricts their exposure and opportunities. Poor documentation and archiving further complicates efforts to trace the authorship, provenance, and ownership of many artworks, undermining both market confidence and cultural preservation efforts.

Rising Material Costs

Artists require special materials to create authentic Thangka and Paubha, most of which they import. The rising price of gold used in these paintings, along with an increase in the price of mineral colors, has forced artists to work with traditional materials. Very few masters remain to create high-quality master pieces, which drives the prices of these artworks, making them less affordable for collectors.

The Impact of Mass Production and Skill Dilution

To meet the growing demand for more affordable artworks, some businesses have resorted to mass production, often disregarding established iconographic and iconometric guidelines. Additionally, the rise of prints with these trends has displaced local artists and jeopardized the authenticity and cultural integrity of traditional art practices.

Questions of Authenticity and Artistic Identity

Rather than individuals, groups of artists paint most of the Nepali Thangka and Paubha. As these artworks are painted to be exported, many artworks are painted in specific country based styles such as Tibetan, Japanese, Korean etc. This has sparked criticism about the authenticity and origin of these artworks. Furthermore, artists often prioritize the spiritual and functional aspects of their work over creativity, which also overshadows their identity.

Efforts and Emerging Solutions

Despite the challenges, Nepal has seen promising efforts to preserve and strengthen Thangka traditions.

Educational Institutions such as Aksheswar Traditional Buddhist Art College affiliated with Lumbini Buddhist University (LBU) offer Nepal’s first bachelor’s degree in traditional Buddhist art. Similarly, shorter vocational programs through Council of Technical Education and Vocational Training (CTEVT), and Federation of Handicraft Associations of Nepal (FHAN) provide additional training opportunities for aspiring artists. Beyond institutions, monastery-based and private household training spaces continue to maintain the traditional Guru-disciple system.

Documentation and Research by early scholars such as Lain Singh Bangdel, Mary Slusser, and Pratapadity Pal helped introduce Nepali Buddhist art traditions to the global audience. Over the years the Department of Archeology, Tribhuvan University, LBU, NAFA, FHAN, and museums like the National Museum, Patan Museum, and Taragaon Next have contributed through publications, exhibitions, and academic research of this art tradition.

Legal Protection is essential for preserving the art. While no law specifically governs these sacred arts, general cultural heritage protection laws, intellectual property frameworks, and export regulations provide partial safeguards.

Digitization and Archiving has gained momentum among scholars, institutions, museums, galleries and artspaces. They have started digitization projects, high-resolution imaging, and create detailed catalogs to digitally preserve artistic and historical context. These efforts increasingly provide researchers, collectors, artists and curators with reliable references that support authentication and verification. This offers new ways to prevent forgery, and protect artists’ rights.

The Himalayan Art Council (HAC) plays a crucial role in preserving and promoting the sacred tradition of Thangka painting in Nepal and the broader Himalayan region. HAC creates digital certificates that guarantee authorship, provenance, and cultural integrity, protecting artists and collectors from forgery while honoring the spiritual origin of each work. Each certified artwork is part of a growing public archive and scholarly resource.

Final Thoughts: Honoring the Living Tradition of Thangka Art

Thangka and Paubha paintings are far more than artistic creations; they are vessels of devotion, knowledge, lineage, and the living spiritual heritage of the Himalayan region. Their survival depends not only on skilled artists and traditional lineages, but also on informed patrons, institutions, and communities who value and protect this sacred art. As interest grows around the world, it becomes increasingly important to support authentic artists, preserve traditional methods, and promote accurate understanding of these profound cultural treasures.

To explore authenticated Thangka and Paubha, support traditional artists, or learn more about preservation initiatives, consider visiting the Himalayan Art Council. Their work helps safeguard these sacred traditions while connecting global audiences with the richness of Himalayan art.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the meaning of Thangka?

A thangka is a sacred Buddhist scroll painting, usually painted on cotton or silk canvas. They usually depict subjects related to Buddhist, Hindu, and Bon philosophies. The term “Thangka” is derived from the Tibetan word thang yig, which means “recorded message” or “thing that one unrolls.”

Who paints Thangka paintings?

Thangka are created by artists who have undergone rigorous training in traditional methods. They could be monastic monks as well as laypeople belonging to the artist community. In Nepal, Newa artists paint Paubha, while Tamang, Hyolmo, and Sherpa communities paint Thangka.

What is the price range of a Thangka painting?

Thangka prices vary widely based on age, size, quality, materials, artist reputation, subject, and condition. Souvenir paintings from emerging artists range from $15-$150. Contemporary works from emerging artists range from $200-$2,000. Established artists using authentic materials charge $2,000-$15,000 and more. Special paintings can cover $15,000-$50,000 or more. The collection of the Himalayan Art Council ranges from $1,000-$52,000.

How long does it take to create a Thangka painting?

Creation time varies by size and complexity. Small, simple works of size 15 x 20 inches require 1-2 months of full-time work. Medium-sized paintings of 18 x 24 inches take 3-6 months. Large paintings with sizes 20 x 30 inches and more with detailed works, particularly complex mandalas or narrative scenes could require 8-12 months and sometimes longer.

Can I commission a custom Thangka with specific iconography?

Yes, this is a long-standing tradition still actively practiced even today in Himalayan region. You can discuss your preference on deities, size, and materials with the artist. They would also suggest proper iconographic features. However, be notified that the custom works usually cost more than ready-made paintings.

How do I know if a Thangka is consecrated?

Besides antique Thangka from monasteries or practicing households, new Thangka are only consecrated once confirmed by a patron or buyer.

Are printed Thangkas accepted for Buddhist practice?

Whether printed or painted, the main purpose of a Thangka is to support visualization and connect the practitioners with their deity of practice. However there is also an argument that a Thangka holds the intention and merit of both patron and artist during creation which cannot be mechanically reproduced. Therefore, while prints may serve for educational or discourse purposes, an authentic hand-painted Thangka would be advised for practice.

Can I hang a Thangka in any room?

Traditionally Thangka are displayed in clean, respectful spaces suitable for sacred objects such as meditational or praying rooms. Nowadays, people also hang Thangka in living rooms, study areas, and bedrooms. However, avoid bathrooms entirely as they are considered impure and kitchens for preservational concerns.